With a small straw, held vertically, blow onto the surface of a puddle. This creates a small, purely radial flow of air that will set the water in motion. An equivalent method is to force the movement from below, with a small stream of water just below the water-air interface.

Another simple way is to change the voltage of the interface on a near-point area. In this case, a Marangoni effect is exploited, which can be chemical or thermal. Anyone who is used to washing dishes by hand has experienced the chemical version: a drop of soap placed on water in a dirty pan instantly clears a light spot on the surface. The thermal version is less commonplace, but hardly less simple. It can be tested on the same pan with a soldering iron whose pane has been cut like a pencil. Just “prick” the surface of the water with the hot tip to cause movement {1}.

In principle, all of these experiences are equivalent, at least qualitatively: the flow generated is expected to exhibit the same radial symmetry as that of the excitation source. The fluid should flow equally in all directions, with the associated velocity field forming a torus of revolution around the source.

This is the expected result under the pure fluid hypothesis (ideally clean water). In reality, the limit of pure fluid is never reached, the water-air interface being always contaminated by traces of surface active elements (TA). Obviously TA is present in abundance in the case of dirty dishes. We can also do the same experiments on a soap film (the one with the straw is described in an article from 1989 {2}). That said, the same remark about flow symmetry is relevant, presence of TA or not.

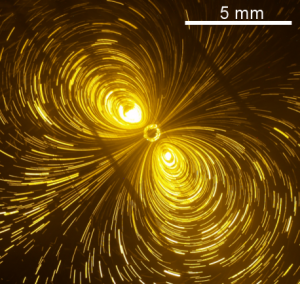

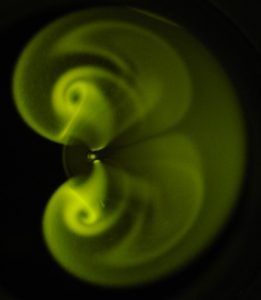

We find in the literature the achievements of these different types of experiments, with sources of excitation of various sizes, from nanometers to centimeters. Radial flows (approximately) are observed, but some spectacular counterexamples are described where the flow is organized in pairs of vortices. We have set up several experiments at the CRPP for a systematic study of the phenomenon, in the mechanical (water jet, Fig. 1) and thermal (with particles heated by laser) versions. We were able to determine the conditions for the appearance of vortices and characterize the related velocity fields. In parallel with the observations, a theoretical study was undertaken, based on the classical equations of hydrodynamics in the Stokes limit (the inertia of the fluid is neglected), from which a numerical simulation was built {3}. Analysis shows that the phenomenon is the result of hydrodynamic instability, a consequence of the coupling between the surface concentration of TA and the speed of the fluid. At low forcing, the flow is (almost) radial. Increasing the forcing leads to a spontaneous breaking of the radial symmetry, with the appearance of one or two pairs of vortices. Important property of the phenomenon: the presence of TA is a necessary condition for instability, but very little is enough. Vortices appear in “pure” water, due only to contamination from exposure to air within minutes.

Among other phenomena that have remained unexplained so far, our analysis allows us to understand how hot particles on the surface of the water, spherical and untreated, behave like hyper-rapid micro-swimmers {4}.

{1} Watch out for safety if you experiment. 220V and water don’t go well together.

{2} Couder et al., On the hydrodynamics of soap films, Physica D 37, 384 (1989).

{3} G. Koleski, J.-C. Loudet, A. Vilquin, B. Pouligny and T. Bickel, Surfactant-driven instability of a divergent flow, to be published in Physical Review Fluids, Editors’ Suggestion.

{4} A. Girot et al., Motion of Optically Heated Spheres at the Water – Air Interface, Langmuir 32, 2687 (2016).

Photographs: Pair of vortices in the water jet experiment (seen from above): on the left, streamlines; on the right, trace (called “Koleski flower”) generated by a drop of dye deposited between the two vortices.

Contact : J.-C. Loudet